nananana = spider in Hawaiian

It is the most “repetitive” word I have ever seen in my whole puff.

Words like that in the Hawaiian language are possible because:

1) It has just 5 vowels (aeiou) and 8 consonants (hklmnpw’)

2) There’s no consonant clusters and after every consonant a vowel has to follow

The scarcity of letters/sounds leads to really intetesting results when foreign words are borrowed into Hawaiian and they are Hawaiianaised:

Palakila = Brazil

Kipalaleka = Gibraltar

Kalikimaka = Christmas

kamepiula = computer

Lopaka = Robert

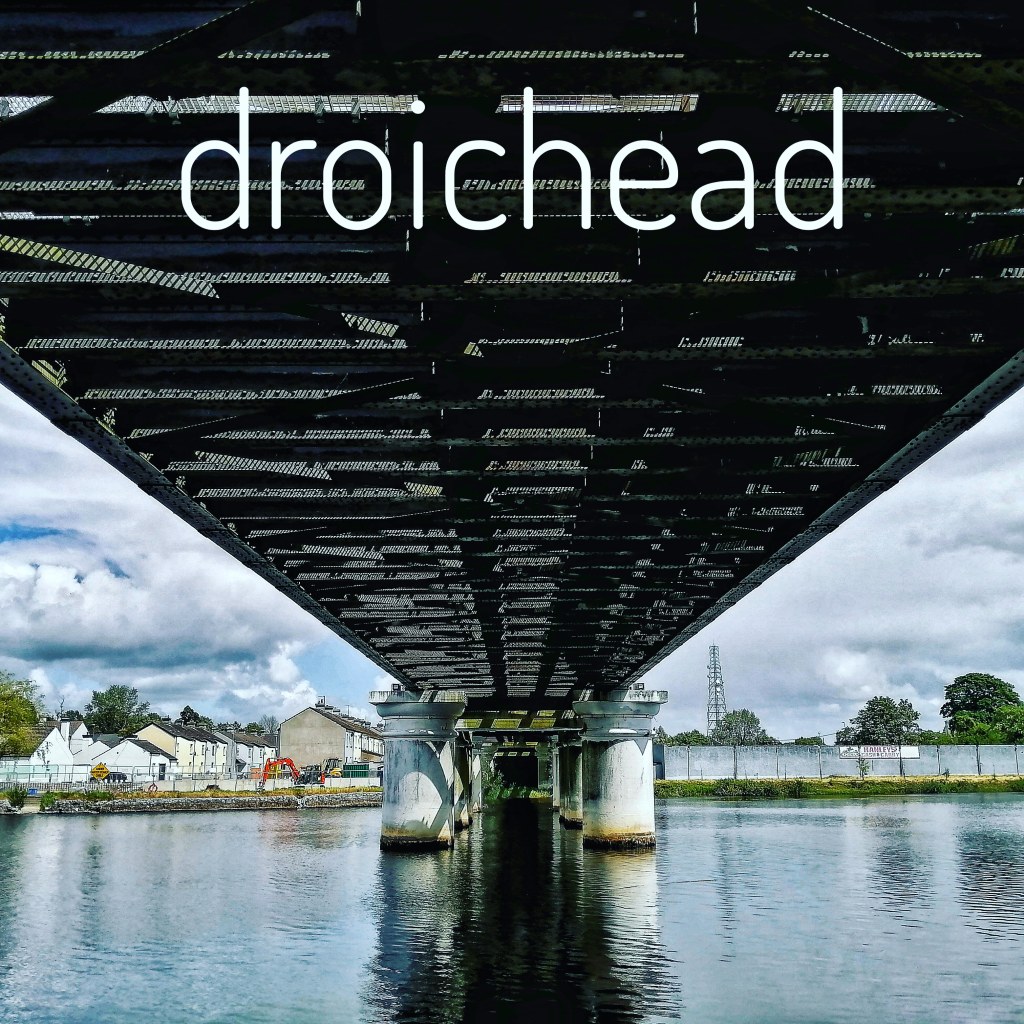

Photo by @lukaszdaciuk (Instagram)

#dailylogorrhoea #logorrhoea #linguistics #words #languages #focail #teangacha #słowa #języki #sanat #kielet #слова #мови #slova #jazyky #kelimeler #diller